Listen to this amazing lady. She’s the founder of PK Silver, and a cancer survivor. Worthwhile listen.

-

Season of Giving

There’s a great guy here in town who volunteers his time in a local church gym to host free indoor volleyball sessions. He sets up three nets, welcomes people, negotiates disputes, and tries to get people to play equitably. All for free. Now that it’s the holiday season, and schedules are a bit more free, the most recent attendance was naturally through the roof…rather out the door. I was having a conversation with someone who was complaining about the record attendance – more than 60 people for three courts. And how it was such a pain to get time to play.

This has always been disturbing to me. A significant population already come to the church with just the expectation of getting to play, without contributing to setup or cleanup (well, not willingly anyway). But this is Christmas. In a church. And if this setting cannot inspire players to give others something they’re getting for free (time on the court), then we have desperately lost the meaning of the season for giving.

Be grateful for all the gifts that you already received. I wish you and yours a happy holiday season, and lessons of kindness and respect.

-

Migration to Volleysensei.com

The Volleysensei content will now live under it’s own domain at VolleySensei.com. To everyone who is subscribed to the blog and are primarily interested in the volleyball related content, please subscribe there.

Thank you.

-

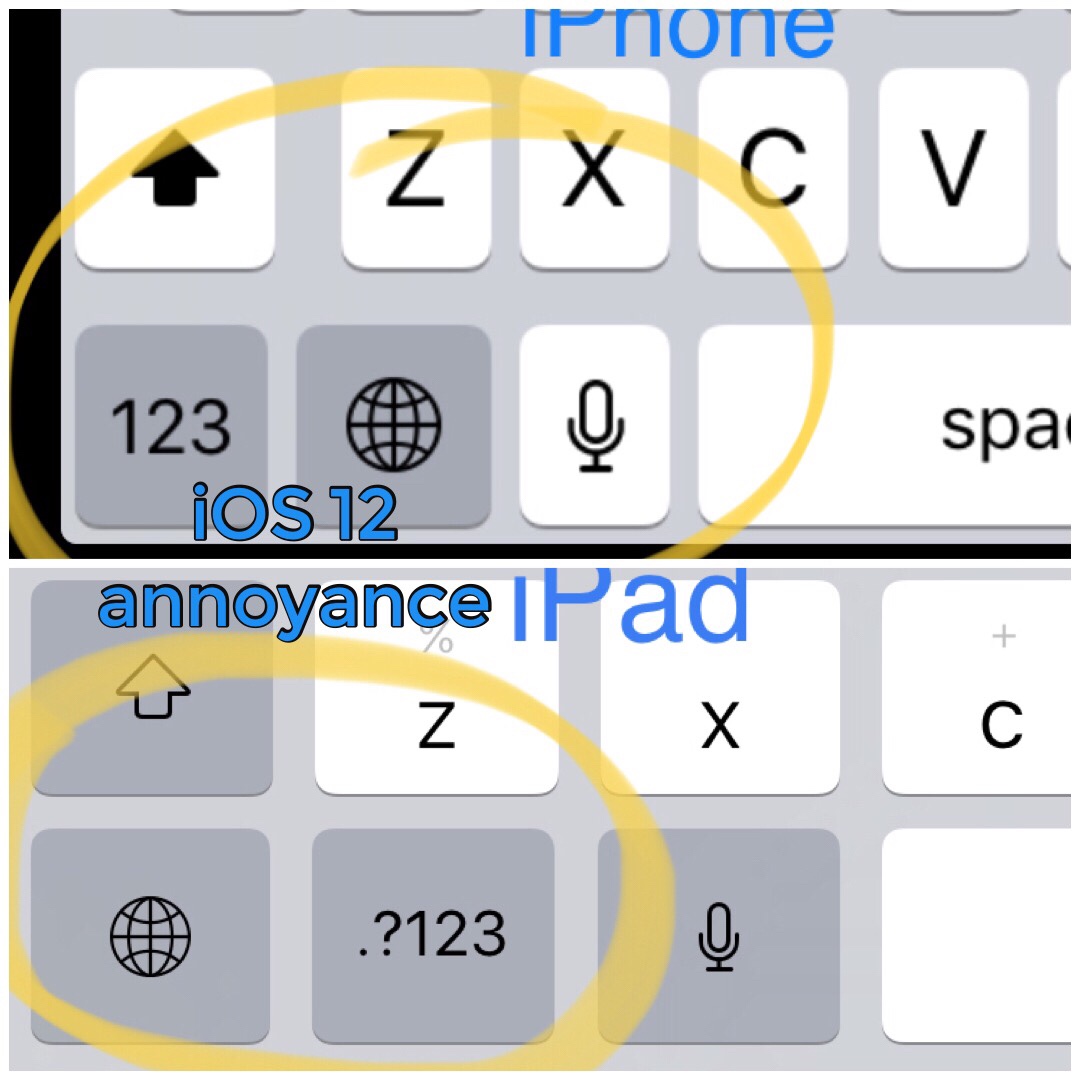

User interface bug

Multi-language support is a key part of modern smartphone operating systems, and in iOS, the operating system for Apple’s mobile devices, it is partly invoked on the keyboard with a “globe” key on the lower left side of the virtual keyboard. In the newest update to iOS, version 12, this placement of the globe key is different depending on if you are using an iPad or an iPhone. Which is intensely annoying. I’d consider this a bug, and may have just missed out if testers didn’t consider switching between language inputs between devices.

-

Visualizing NCAA GPA data

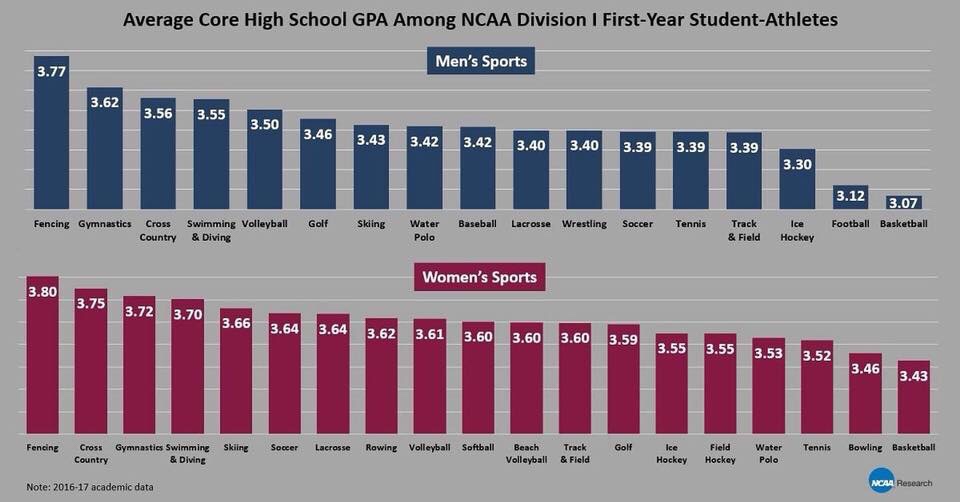

On 5 Sept 2018, the NCAA Research team tweeted out this chart :

It reports the average core high school grade point averages (GPA) among NCAA Division I freshman student athletes. So, a bit of a background – the National Collegiate Athletics Association governs just about all collegiate athletic programs in America, and the Division I schools devote the most money and resources to their athletic programs. A great deal of attention is thus focused on the Division I programs, almost to the detriment of the others (it goes all the way to Division III). The GPA is usually used as a measure of academic performance, though it may not reflect the difficulty of the coursework. But this chart is an egregious use of “infographics” to mislead rather than to bring insight to data:

- Without a Y-axis to denote scale, the use of bar charts here visually make it appear that 3.77 is 7x higher than 3.07, when it’s actually far smaller in scale on standard 4.0 GPA scales (it tops out at 4).

- The categorical use of the different sports makes it appear that it is the independent variable, and that GPA is what is being measured. But since the GPA was measured in high school, it actually precedes the sport.

- Because of this switch in dependent and independent variables, a reader may interpret some form of causality – implying for example that choosing fencing will lead to better academic performance.

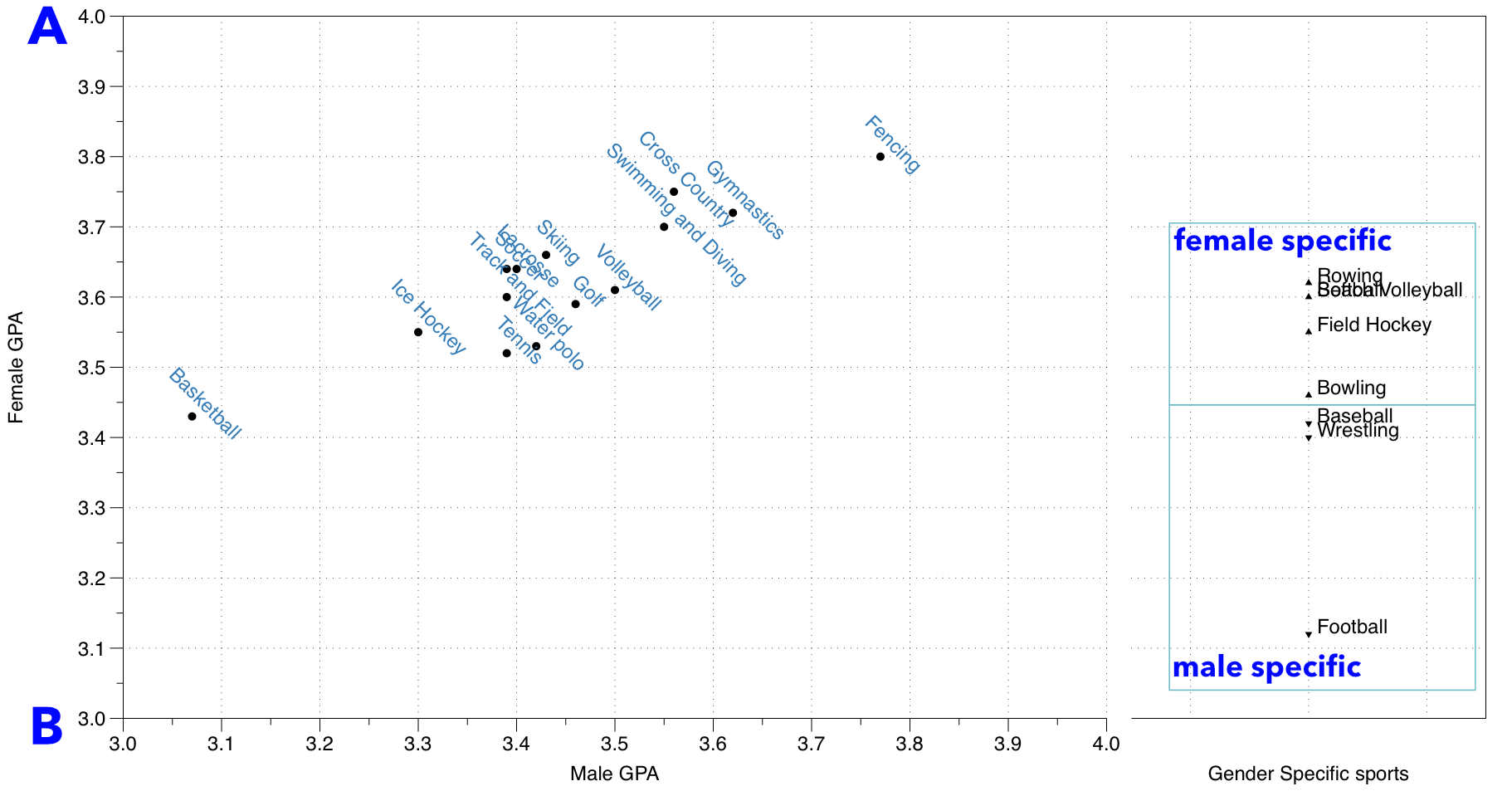

Good data visualization should serve to bring new insight to the data that isn’t evident from just looking at the numbers. The GPAs considered here range between 3-4, which is letter grade B-A, quite above average academically, and that is unsurprising. These are the high school GPAs of student athletes recruited to Division I schools, arguably the most competitive programs. This is a measure of their past academic performance, but doesn’t say anything about how the sport chosen affects their current or future performance. The data, however, informs something about the sports programs themselves. Using the exact same data, I replotted the chart.

The chart is in two parts – on the left is the section where a sport is available for both males and females, and on the right is a smaller section for sports that are gender specific. The axes go from 3.0 to 4.0, indicating the spread within this range. Sports are labeled accordingly.

A linear relationship exists between enrolled female and male student athlete high school GPAs – regardless of sport program. What this means is that at least within each sport, they apply their GPA criteria roughly with the same proportion to both genders. Which probably means that the sports programs recruit from the same communities for both men and women, that is fencing programs put a heavier emphasis on high GPAs for admission than basketball programs do, regardless of gender. But we see a stark difference in the GPA cutoffs between genders: almost all athletic programs recruit females with a GPA above 3.5, while more than half athletic programs enrolled male student athletes with GPAs below 3.5. In fact, all the male specific sport programs – baseball, wrestling and football – recruit with GPAs below 3.5. One cannot make definitive interpretations without further details on how the data is collected, but this implies that the barrier to entry to a collegiate athletic program, at least based on GPA, is significantly lower for males than for females. While some may think that this indicates superior academic performance among female student athletes, it could be an indicator for a systemic bias when recruiting for women across all sports programs.

-

Homographic terms

Many terms in athletic coaching are poorly defined yet form the basis of disagreements. For example, the word athletic is really not quantifiable, and describes some quality that cannot be calibrated, yet is used as a basis of comparing people. In volleyball, the idea of ball control is heavily valued, is generally thought be observable, but different people will have different specific ideas as to what constitutes having ball control, or how to measure it.

Homographic (despite the potentially juvenile interpretation) refer to situations where the same word can carry multiple meanings, and thus be confused between concepts, often leading to disagreements because each party was actually thinking of a different meaning for that word. For example, the word fly can be used both as a noun and a verb, each one carrying radically different meanings.

But a more subtle disagreement comes with blocking. Blocking refers to both a technique and a strategy. For stat collection purposes, in beach volleyball, a block is only recorded when a player earns a point by jumping up and intercepting a ball at the net. Consequently, this technique is confused with the whole strategy of blocking, which is a component of defense that limits the offensive options of the opposing team. Blocking actions that serve to guide the ball out or into the convertible control of the team are just as valuable as a stuff block. The technique of blocking is thus simply one of the options of the strategy of blocking. Good blockers consider all the available tools for the strategy. A jumping blocker that knocks the ball out of the defensive arena simply introduces unnecessary unpredictability. An effective blocker may never jump at all, and still control the attack options of the other team, and the contribute to the point conversion opportunities.

Google Image result for volleyball setting Another term with homographic confusion between a technique and a strategy is setting – the popular image of volleyball setting (at least as unscientifically assayed through Google Images) is the distinct technique hand setting. Operationally, though, setting is a strategy of establishing the offensive opportunities for the team, and, as with blocking, the technique of hand setting is merely one of the many factors that figure into the strategy of good setting. One who can execute the technique of a hand setting well is not necessarily a good strategic setter. Conversely, good strategic setting should have a broad range of control techniques to carry options for efficient point scoring. Unfortunately, much of the dialog conflates the two meanings of setting, leading to this notion that one can judge the strategic value of a setter simply by evaluating the execution of the technique.

-

Volleyball and Newton

I ignited a fierce debate a few months back by simply asking:

“the higher you jump, the more force you land with, right? (Yes, it’s a trick question)”

I posed the question shortly after the McKibbin Brothers released their video on dealing with knee pain, and a trainer was explaining that you could land with up to 5x body weight in force (about 45 seconds into the video) – which then rolls into this rabbit hole about the equivalent of elephants on your knees. Now how could this be?

So, a lot of this comes from the incorrect use of the term “force”. Basic physics, which most people should know, force acting on an object is defined by it’s mass multiplied by its acceleration, or

Force =mass x acceleration

In most cases, we are talking about the force of gravity, which imparts the same acceleration to objects regardless of their mass (which is why in a vacuum, a feather and a bowling ball will fall at the same rate). This is an appropriate situation, because for a jumping athlete, that impact with the ground is really the same question about falling from different heights. So, what is acceleration? Acceleration is a change in velocity over time. The higher up you are, the more time gravity has to affect you, and so by the time you get to the ground, your velocity is higher. But what happens on impact? The velocity changes, from whatever it is imparted by gravity, to zero. This, too is a type of acceleration, and it’s this acceleration where the force comes from. So, let’s look at this equation again:

F=ma = m (starting velocity-ending velocity)/time

if we rearrange it:

F x time = mass x change in velocity

The missing element in this discussion is how much time is being taken to bring the falling athlete to rest. Since mass and the change in velocity aren’t changing, we need to look at the relationship between time and the amount of force applied. The assumption in all the landing measurements is that the athlete stops on contact with the ground – hence, time is set to be very small. Thus, the amount of force goes up to effect the same change in velocity (the term, I believe, is impulse). But if we are able to extend the amount of time landing, the force acting can go down.

It’s like dropping your phone from various heights. But how can a protective case allow it to drop without as much damage? That’s because parts of the phone can continue to fall as the case deforms, increasing time, decreasing force, and protecting the phone itself. Likewise, the flaw in the force plate measurements is not considering that a body is an elastic object and can redistribute the energy of impact. It only measures the force based on a very short period of time, and that will bring the force measurement up.

In sand, since falling time continues longer than on an inelastic force plate, the force will decrease. But there are still more things to do to dissipate that energy of impact. Now will those exercises actually help? That’s a discussion for another day.

-

How do you want your set?

I hear a number of common phrases during volleyball play which I discourage athletes from using. This is why.

“How do you want your set?”

Often advised for new teammates, this question is poorly worded and really does not address what is important for the game. What an attacker wants for a set is often pretty different from what she needs in an in game situation. Moreover, the expected answer is often couched in terms of trajectory and distance from the net; it is only applicable in a blocked and controlled passing situation. It can result in some pretty impressive “warm up” hits, but doesn’t necessarily translate to reality.

The question does reveal something about the setter – the idea of subservience to the attacker, and that ultimately it’s the attacker’s desires that fuel the point earning potential. In this question, the setter outsources his judgment and decision making to the attacker. It lowers the bar, the idea that as long as the setter can deliver along synthetic parameters, he has earned success, even if the team loses the point.

Looking into the characteristics of a good set, most athletes will define it as some kind behavior of the ball, adjusted with respect to the net. But how effective an attack becomes is contextual to the attacker and the situation. The characteristics of a good set are not easily described between just the setter and the ball, but ultimately it’s the ability of the setter to take responsibility for the options available for her partner that determines the outcome. Falling back onto this question is rejecting that responsibility; the partner cannot really meaningfully answer it, and just describes a desire for a quick answer to a complex question. Let go of the crutch, and understand that good setting is a process – the attack is the outcome.

-

Becoming height neutral

The website Beachvolleyballspace covered the recent FIVB Gstaad Major with an article celebrating the winners, the currently top ranked Canadian team of Paredes and Pavan claiming the gold. The article title (Canadian women dominate Gstaad Major – Japan challenges top teams) makes special mention of the fifth place Japanese team of Murakami and Ishii. Why? Was it a remarkable breakthrough performance?

The whole latter half was spent mentioning how much shorter the team was relative to their opponents. That’s it. Beach volleyball culture venerates height so much that it’s often the first and only statistic mentioned for players. No mention that Murakami is a 7 year veteran of the FIVB circuit – it’s newsworthy because they were supposed to lose.

Height discrimination is so pervasive that coaches will refuse to consider athletes just for being too short. I’ve spoken with talented young women who have already given up the dream of playing beach volleyball for college because they’ve been told time and again that their genetics will simply not give them a chance. Players constantly pine about being taller, and taller players, regardless of experience, are always groomed. A metric this damning should be backed by extensive studies or data – yet every discussion I’ve had with coaches either point to anecdotal experience, or cherrypicked material. Saying that the best athletes in the world are always taller is flawed logic – they are the product of this pervasive bias, so of course the selection for taller players is evident. What’s more telling is that despite this, players of all sizes break through: Bruno Schmidt, Shelda Bede, Holly McPeak, Annie Martin. If the thesis is that height is always a beach volleyball advantage, these counterexamples are sufficient to discredit it.

The cultural baggage of height superiority is entrained from a young age, and repeated incessantly – thus, how height becomes an advantage stems from a psychological one. Taller players are simply given more opportunities to play, to explore, to make mistakes. Pay attention without bias next time, and see the language difference between how coaches treat taller and shorter players, and how they treat each other. A shorter team hands to the taller team an immediate advantage by simply expecting themselves to be at a disadvantage. The way out of this is to begin young, and to start instilling in them the confidence of height neutrality. Even among older athletes, we can unlock a richer vein of talent from our pool of players by simply opening our eyes beyond how tall they stand or how high they jump. The game is deeper and wider than the height of its tallest players.

-

Earned or Found

I was having this discussion once about buying chicken. My friend was of the opinion that there are just superior sources of birds, and that one should judge a restaurant already by knowing where they buy their chicken. My position was that it was a poor measure of the skill of chef – after all, where true mastery lies is in extracting a delicious dish from what’s considered inferior ingredients. It’s what our grandmothers have honed through a lifetime of experience – making do with what was available, and still nurturing their families. At the end of the day, when those fancy chefs need inspiration, they go to learn from those grandmas and aunties.

When I encounter conversations among volleyball coaches, I hear echoes of this conversation. There’s immediate talk about how this player is tall, or that player is athletic, or if that other player has that relentless competitiveness to pursue the ball – and that of course, they should be the first picks when being trained. But how is that the measure of the coach? In many circles, by only considering the win-loss record of a squad, the measure of a coach is that of a prospector, that if they can just find the right pieces already pre formed, or that it just needs a little polishing, they can win and be rewarded. For all that is preached about growth mindset, coaches often fail to accept the challenge of being mentors and teachers, of seeing the murkiest glimmer of potential and bringing it forward.

And maybe some of that is inherent in the reward system that doesn’t see the historical context of good athletes, or how we judge beach volleyball players on individual performance versus team contexts – and how they were trained in either. In a sense, the outcome of good competent coaching is to make the role of the coach invisible. Much like how our grandmothers simply dished out miracle after miracle from their meager cupboards that we take for granted – as we rain accolades on the preening chefs that cannot be bothered with the cheap cuts.